-

- Bastides bienvenue :

- .

- Villes Neuves

- en EUROPE :

- Présentation générale

- France

- Espagne

- Grande Bretagne

- Italie

- Pologne

- Portugal

- Suisse

- Scandinavie : -Finlande

- **Recherche : Interreg

- .

- hors d'EUROPE,

- Amérique

- Afrique

- Asie

- .

- Bastides:

- 1- tableau des "modèles"

- 2- ..Libourne. ..Monpazier..Monflanquin.

- ..Vianne..Villeneuve/Lot

- Bastides Gironde.

- .

- *

- Définition de "Bastide",

- leurs caractéristiques,

- leurs Chartes.

- Le Tracé orthogonal,

- la Place,

- la Halle,

- les Maisons,

- les Cornières un problème,

- les Andrones,

- L'église

- les Remparts : avec ou sans.

- Chateau : avec ou sans

- Puits et ponts

- Bastides Modèles.

- Contexte historique.

- .

- Présentation par :

- Cartographie

- Musée des Bastides,

- Centre Etude Bastides,

- Bibliographie,

- Glossaire,

- Toponymie

- .

- Bastides Répertoire

- par fondateurs:

- Cisterciens

- par départements,

- sur sites internet

- par bastides :

- A à M

- N à V

- par Thèmes

- .

- L'orthogonalité :

- dans l'Antiquité,

- dans la théorie.

- dans les arts

- .

- *

- Annexes sur :

- les villes en étoile,

- les "circulades",

- Sauvetés et castelnaus

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ancient Town-Planning, by F. Haverfield This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Ancient Town-Planning Author: F. Haverfield Release Date: November 28, 2004 [EBook #14189] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ANCIENT TOWN-PLANNING *** Produced by Ted Garvin and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team

STREETS IN TIMGAD

From a photograph.

ANCIENT TOWN-PLANNING

By

F. HAVERFIELD

Oxford

at The Clarendon Press

1913

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

London • Edinburgh • Glasgow • New York

Toronto • Melbourne • Bombay

HUMPHREY MILFORD

Publisher to the University

PREFACE

The following pages are an enlargement of a paper read to the University of London as the Creighton Lecture for 1910, and also submitted in part to the London Conference on Town-planning in the same year.

The original lecture was written as a scholar's contribution to a modern movement. It looked on town-planning as one of those new methods of social reform, which stand in somewhat sharp contrast with the usual aims of political parties and parliaments. The latter concern mainly the outward and public life of men as fellow-citizens in a state; they involve such problems as Home Rule, Disestablishment, Protection. The newer ideals centre round the daily life of human beings in their domestic environment. Men and women—or rather, women and men—have begun to demand that the health and housing and food and comfort of mankind, and much else that not long ago seemed to lie outside the scope of legislation, should be treated with as close attention and logic and intelligence as any of the older and more conventional problems of politicians. They will not leave even the tubes of babies' feeding-bottles to an off-hand opportunism.

Among these newer efforts town-planning is one of the better known. Most of us now admit that if some scores of dwellings have to be run up for working-men or city-clerks—or even for University teachers in North Oxford—they can and should be planned with regard to the health and convenience and occupations of their probable tenants. Town-planning has taken rank as an art; it is sometimes styled a science and University professorships are named after it; in the London Conference of 1910 it got its deductio in forum or at least its first dance. But it is still young and its possibilities undefined. Its name is apt to be applied to all sorts of building-schemes, and little attempt is made to assign it any specific sense. It is only slowly making its way towards the recognized method and the recognized principles which even an art requires. Here, it seemed, a student of ancient history might proffer parallels from antiquity, and especially from the Hellenistic and Roman ages, which somewhat resemble the present day in their care for the well-being of the individual.

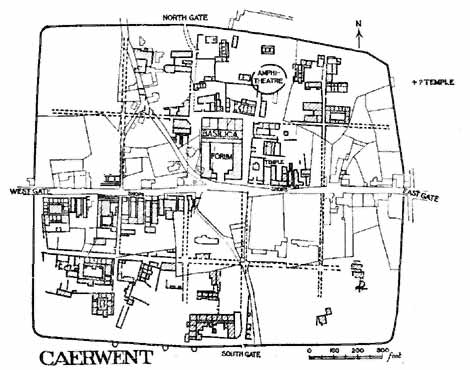

In enlarging the lecture I have tried not only to preserve this point of view, but also to treat the subject in a manner useful to classical scholars and historians. The details of Greek and Roman town-planning are probably little known to many who study Greek and Roman life, and though they have often been incidentally discussed,[1] they have never been collected. The material, however, is plentiful, and it illuminates vividly the character and meaning of that city-life which, in its different forms, was a vital element in both the Greek and the Roman world. Even our little towns of Silchester and Caerwent in Roman Britain become more intelligible by its aid. The Roman student gains perhaps more than the Hellenist from this inquiry, since the ancient Roman builder planned more regularly and the modern Roman archaeologist has dug more widely. But admirable German excavations at Priene, Miletus, and elsewhere declare that much may be learnt about Greek towns and in Greek lands.

The task of collecting and examining these details is not easy. It needs much local knowledge and many local books, all of which are hard to come by. Here, as in most branches of Roman history, we want a series of special inquiries into the fortunes of individual Roman towns in Italy and the provinces, carried out by men who combine two things which seldom go together, scientific and parochial knowledge. But a body of evidence already waits to be used, and though its discussion may lead—as it has led me—into topographical minutiae, where completeness and certainty are too often unattainable and errors are fatally easy, my results may nevertheless contain some new suggestions and may help some future workers.

I have avoided technical terms as far as I could, and that not merely in the interests of the general reader. Such terms are too often both ugly and unnecessary. When a foreign scholar writes of a Roman town as 'scamnirt' or 'strigirt', it is hard to avoid the feeling that this is neither pleasant nor needful. Perhaps it is not even accurate, as I shall point out below. I have accordingly tried to make my text as plain as possible and to confine technicalities to the footnotes.

F.H.

CONTENTS

- LIST OF PLANS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

- TABLE OF MEASURES

- 1. PRELIMINARY REMARKS ON ANCIENT TOWN-PLANNING

- 2. GREEK TOWN-PLANNING. THE ORIGINS: BABYLON

- 3. GREEK TOWN-PLANNING. FIRST EFFORTS

- 4. GREEK TOWN-PLANNING. THE MACEDONIAN AGE

- 5. ITALY. THE ORIGINS

- 6. ITALY. THE LATE REPUBLIC AND EMPIRE

- 7. ITALIAN TOWNS

- 8. ROMAN PROVINCIAL TOWNS. I

- 9. ROMAN PROVINCIAL TOWNS. II

- 10. ROMAN BUILDING LAWS

- 11. THE SEQUEL

- APPENDIX. TOWN-PLANNING IN CHINA

- INDEX

LIST OF PLANS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

(For precise references to sources see the various footnotes.)

For the loan of blocks I am indebted to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (fig. 21), to the German Imperial Archaeological Institute (fig. 9), to the Royal Geographical Society (fig. 36), and to the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Editors of the Transactions of the Town-Planning Conference, 1911 (figs. 7, 8, 17, 30, 32, 35). Fig. 11 is from Mr. T.E. Peet's Stone and Bronze Ages in Italy. The other 26 blocks have been prepared for this volume.

TABLE OF MEASURES

The following figures may be found convenient by readers who wish to take special account of the dimensions cited in the following pages, and may also help them to correct any errors which I have unwittingly admitted.

1 Roman foot = 0.296 metres = 0.97 English feet.

For practical purposes 100 Roman feet = 97 English feet.

1 Iugerum = 120 x 240 Roman feet = 116.4 x 233.8 English

feet.

For practical purposes a Iugerum may be taken to be rather over 2/3 of an

acre and rather over ¼ of a hectare, and more exactly 2523.3 sq. metres.

1 Metre = 1.09 English yards, a trifle less than 40 ins. 402.5 metres equal a quarter of a mile.

1 Hectare (10000 sq. metres) = 2.47 acres (11955 sq. yds.).

1 Acre = nearly 69½ x 69½ yds. (208.7 ft. square) = 4840 sq. yds.

CHAPTER I

PRELIMINARY REMARKS

Town-planning—the art of laying out towns with due care for the health and comfort of inhabitants, for industrial and commercial efficiency, and for reasonable beauty of buildings—is an art of intermittent activity. It belongs to special ages and circumstances. For its full unfolding two conditions are needed. The age must be one in which, whether through growth, or through movements of population, towns are being freely founded or freely enlarged, and almost as a matter of course attention is drawn to methods of arranging and laying out such towns. And secondly, the builders of these towns must have wit enough to care for the well-being of common men and the due arrangement of ordinary dwellings. That has not always happened. In many lands and centuries—in ages where civilization has been tinged by an under-current of barbarism—one or both of these conditions have been absent. In Asia during much of its history, in early Greece, in Europe during the first half of the Middle Ages, towns have consisted of one or two dominant buildings, temple or church or castle, of one or two processional avenues for worshippers at sacred festivals, and a little adjacent chaos of tortuous lanes and squalid houses. Architects have devised beautiful buildings in such towns. But they have not touched the chaos or treated the whole inhabited area as one unit. Town-planning has been here unknown.[2]

In other periods towns have been founded in large numbers and full-grown or nearly full-grown, to furnish homes for multitudes of common men, and their founders have built them on some plan or system. One such period is, of course, our own. Within the last half-century towns have arisen all over Europe and America. They are many in number. They are large in area. Most of them have been born almost full-grown; some have been established complete; others have developed abruptly out of small villages; elsewhere, additions huge enough to form separate cities have sprung up beside towns already great. Throughout this development we can trace a tendency to plan, beginning with the unconscious mechanical arrangements of industrial cities or suburbs and ending in the conscious efforts of to-day.

If we consider their size and their number together, these new European and American towns surpass anything that the world has yet seen. But, save in respect of size, the process of founding or enlarging towns is no new thing. In the old world, alike in the Greek lands round the eastern Mediterranean and in the wide empire of Rome, urban life increased rapidly at certain periods through the establishment of towns almost full-grown. The earliest towns of Greece and Italy were, through sheer necessity, small. They could not grow beyond the steep hill-tops which kept them safe, or house more inhabitants than their scanty fields could feed.[3] But the world was then large; new lands lay open to those who had no room at home, and bodies of willing exiles, keeping still their custom of civil life, planted new towns throughout the Mediterranean lands. The process was extended by state aid. Republics or monarchs founded colonies to extend their power or to house their veterans, and the results were equally towns springing up full-grown in southern Europe and, western Asia and even northern Africa. So too in remoter regions. Obscure evidence from China suggests that there also in early times towns were planted and military colonies were sent to outlying regions on somewhat the same methods as were used by the Greeks and Romans.

Even under less kindly conditions, the art has not been wholly dormant. Special circumstances or special men have called it into brief activity. The 'bastides' and the 'villes neuves' of thirteenth-century France were founded at a particular period and under special circumstances, and, brief as the period was and governed by military urgencies, they were laid out on a more or less definite plan (p. 143). The streets designed by Wood at Bath about 1735, by Craig at Edinburgh about 1770, by Grainger at Newcastle about 1835, show what individual genius could do at favourable moments. But such instances, however interesting in themselves, are obviously less important than the larger manifestations of town-planning in Greece and Rome.

In almost all cases, the frequent establishment of towns has been accompanied by the adoption of a definite principle of town-planning, and throughout the principle has been essentially the same. It has been based on the straight line and the right angle. These, indeed, are the marks which sunder even the simplest civilization from barbarism. The savage, inconsistent in his moral life, is equally inconsistent, equally unable to 'keep straight', in his house-building and his road-making. Compare, for example, a British and a Roman road. The Roman road ran proverbially direct; even its few curves were not seldom formed by straight lines joined together. The British road was quite different. It curled as fancy dictated, wandered along the foot or the scarp of a range of hills, followed the ridge of winding downs, and only by chance stumbled briefly into straightness. Whenever ancient remains show a long straight line or several correctly drawn right angles, we may be sure that they date from a civilized age.

In general, ancient town-planning used not merely the straight line and the right angle but the two together. It tried very few experiments involving other angles. Once or twice, as at Rhodes (pp. 31, 81), we hear of streets radiating fan-fashion from a common centre, like the gangways of an ancient theatre or the thoroughfares of modern Karlsruhe, or that Palma Nuova, founded by Venice in 1593 to defend its north-eastern boundaries, which was shaped almost like a starfish. But, as a rule, the streets ran parallel or at right angles to each other and the blocks of houses which they enclosed were either square or oblong.

Much variety is noticeable, however, in details. Sometimes the outline of the ancient town was square or almost square, the house-blocks were of the same shape, and the plan of the town was indistinguishable from a chess-board. Or, instead of squares, oblong house-blocks formed a pattern not strictly that of a chess-board but geometrical and rectangular. Often the outline of the town was irregular and merely convenient, but the streets still kept, so far as they could, to a rectangular plan. Sometimes, lastly, the rectangular planning was limited to a few broad thoroughfares, while the smaller side-streets, were utterly irregular. Other variations may be seen in the prominence granted or refused to public and especially to sacred buildings. In some towns full provision was made for these; ample streets with stately vistas led up to them, and open spaces were left from which they could be seen with advantage. In others there were neither vistas nor open spaces nor even splendid buildings.

A measure of historical continuity can be traced in the occurrence of these variations. The towns of the earlier Greeks were stately enough in their public buildings and principal thoroughfares, but they revealed a half-barbaric spirit in their mean side-streets and unlovely dwellings. In the middle of the fifth century men rose above this ideal. They began to recognize private houses and to attempt an adequate grouping of their cities as units capable of a single plan. But they did not carry this conception very far. The decorative still dominated the useful. Broad straight streets were still few and were laid out mainly as avenues for processions and as ample spaces for great facades.[4] Private houses were still of small account. The notion that the City was the State, helpful and progressive as it was, did something also to paralyse in certain ways the development of cities.

A change came with the new philosophy and the new politics of the Macedonian era. The older Greek City-states had been large, wealthy, and independent; magnificent buildings and sumptuous festivals were as natural to them as to the greater autonomous municipalities in all ages. But in the Macedonian period the individual cities sank to be parts of a larger whole, items in a dominant state, subjects of military monarchies. The use of public buildings, the splendour of public festivals in individual cities, declined. Instead, the claims of the individual citizen, neglected too much by the City-states but noted by the newer philosophy, found consideration even in town-planning. A more definite, more symmetrical, often more rigidly 'chess-board' pattern was introduced for the towns which now began to be founded in many countries round and east of the Aegean. Ornamental edifices and broad streets were still indeed included, but in the house-blocks round them due space and place were left for the dwellings of common men. For a while the Greeks turned their minds to those details of daily life which in their greater age they had somewhat ignored.

Lastly, the town-planning of the Macedonian era combined, as I believe, with other and Italian elements and formed the town system of the later Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. As in art and architecture, so also in city-planning, the civilization of Greece and of Italy merged almost inextricably into a result which, with all its Greek affinities, is in the end Roman. The student now meets a rigidity of street-plan and a conception of public buildings which are neither Greek nor Oriental. The Roman town was usually a rectangle broken up into four more or less equal and rectangular parts by two main streets which crossed at right angles at or near its centre. To these two streets all the other streets ran parallel or at right angles, and there resulted a definite 'chess-board' pattern of rectangular house-blocks (insulae), square or oblong in shape, more or less uniform in size. The streets themselves were moderate in width; even the main thoroughfares were little wider than the rest, and the public buildings within the walls were now merged in the general mass of houses. The chief structure, the Forum, was an enclosed court, decorated indeed by statues and girt with colonnades, but devoid of facades which could dominate a town. The town councils of the Roman world were no more free than those of Greece or modern England from the municipal vice of over-building. But they had not the same openings for error. On the other hand, there was in most of them a good municipal supply of water, and sewers were laid beneath their streets.

The reason for all this is plain. These Roman towns, even more than the Greek cities of the Macedonian world, were parts of a greater whole. They were items in the Roman Empire; their citizens were citizens of Rome. They had neither the wealth nor the wish to build vast temples or public halls or palaces, such as the Greeks constructed. Their greatest edifices, the theatre and the amphitheatre, witness to the prosperity and population not so much of single towns as of whole neighbourhoods which flocked in to periodic performances.[5] But these towns had unity. Their various parts were, in some sense, harmonized, none being neglected and none grievously over-indulged, and the whole was treated as one organism. Despite limitations which are obvious, the Roman world made a more real sober and consistent attempt to plan towns than any previous age had witnessed.

CHAPTER II

GREEK TOWN-PLANNING. THE ORIGINS, BABYLON

The beginnings of ideas and institutions are seldom well known or well recorded. They are necessarily insignificant and they win scant notice from contemporaries. Town-planning has fared like the rest. Early forms of it appear in Greece during the fourth and fifth centuries B.C.; the origin of these forms is obscure. The oldest settlement of man in town fashion which has yet been explored in any land near Greece is that of Kahun, in Egypt, dating from about 2500 B.C. Here Professor Flinders Petrie unearthed many four-roomed cottages packed close in parallel oblong blocks and a few larger rectangular houses: they are (it seems) the dwellings of the workmen and managers busy with the neighbouring Illahun pyramid.[6] But the settlement is very small, covering less than 20 acres; it is not in itself a real town and its plan has not the scheme or symmetry of a town-plan. For that we must turn to western Asia, to Babylonia and Assyria.

Here we find clearer evidence. The great cities of the Mesopotamian plains show faint traces of town-planning datable to the eighth and following centuries, of which the Greeks seem to have heard and which they may have copied. Our knowledge of these cities is, of course, still very fragmentary, and though it has been much widened by the latest German excavations, it does not yet carry us to definite conclusions. The evidence is twofold, in part literary, drawn from Greek writers and above all Herodotus, and in part archaeological, yielded by Assyrian and Babylonian ruins.

The description of Babylon given by Herodotus is, of course, famous.[7] Even in his own day, it was well enough known to be parodied by contemporary comedians in the Athenian theatre. Probably it rests in part on first-hand knowledge. Herodotus gives us to understand that he visited Babylon in the course of his many wanderings and we have no cause to distrust him; we may even date his visit to somewhere about 450 B.C. He was not indeed the only Greek of his day, nor the first, to get so far afield. But his account nevertheless neither is nor professes to be purely that of an eyewitness. Like other writers in various ages,[8] he drew no sharp division between details which he saw and details which he learnt from others. For the sake (it may be) of vividness, he sets them all on one plane, and they must be judged, not as first-hand evidence but on their own merits.

Babylon, says Herodotus, was planted in an open plain and formed an exact square of great size, 120 stades (that is, nearly 14 miles) each way; the whole circuit was 480 stades, about 55 miles. It was girt with immense brick walls, 340 ft. high and nearly 90 ft. thick, and a broad deep moat full of water, and was entered through 100 gates; presumably we are intended to think of these gates as arranged symmetrically, 25 in each side. From corner to corner the city was cut diagonally by the Euphrates, which thus halved it into two roughly equal triangles, and the river banks were fortified by brick defences—less formidable than the main outer walls—which ran along them from end to end of the city. There was, too, an inner wall on the landward side. The streets were also remarkable:

'The city itself (he says) is full of houses, three or four storeys high, and has been laid out with its streets straight, notably those which run at right angles, that is, those which lead to the river. Each road runs to a small gate in the brick river-wall: there are as many gates as lanes.'[9]

In each part of the city (that is, on either bank of the Euphrates) were specially large buildings, in one part the royal palaces, in the other the temple of Zeus Belos, bronze-gated, square in outline, 400 yards in breadth and length.

So far, in brief, Herodotus. Clearly his words suggest town-planning. The streets that ran straight and the others that ran at right angles are significant enough, even though we may doubt exactly what is meant by these other streets and what they met or cut at right angles. But his account cannot be accepted as it stands. Whatever he saw and whatever his accuracy of observation and memory, not all of his story can be true. His Babylon covers nearly 200 square miles; its walls are over 50 miles long and 30 yds. thick and all but 120 yds. high; its gates are a mile and a half apart. The area of London to-day is no more than 130 square miles, and the topmost point of St. Paul's is barely 130 yds. high. Nanking is the largest city-site in China and its walls are the work of an Empire greater than Babylon; but they measure less than 24 miles in circuit, and they are or were little more than 30 ft. thick and 70 ft. high.[10] Moreover, Herodotus's account of the walls has to be set beside a statement which he makes elsewhere, that they had been razed by Darius sixty or seventy years before his visit.[11] The destruction can hardly have been complete. But in any case Herodotus can only have seen fragments, easily misinterpreted, easily explained by local ciceroni as relics of something quite unlike the facts.

Turn now to the actual remains of Babylon, as known from surveys and excavations. We find a large district extending to both banks of the Euphrates, which is covered rather irregularly by the mounds of many ruined buildings. Two sites in it are especially notable. At its southern end is Birs Nimrud and some adjacent mounds, anciently Borsippa; here stood a huge temple of the god Nebo. Near its north end, ten or eleven miles north of Borsippa, round Babil and Kasr, is a larger wilderness of ruin, three miles long and nearly as broad in extreme dimensions; here town-walls and palaces of Babylonian kings and temples of Babylonian gods and streets and dwelling-houses of ordinary men have been detected and in part uncovered. Other signs of inhabitation can be traced elsewhere in this district, as yet unexplored.

Not unnaturally, some scholars have thought that this whole region represents the ancient Babylon and that the vast walls of Herodotus enclosed it all.[12] This view, however, cannot be accepted. Quite apart from the considerations urged above, the region in question is not square but rather triangular, and traces of wall and ditch surrounding it are altogether wanting, though city-walls have survived elsewhere in this neighbourhood and though nothing can wholly delete an ancient ditch. We have, in short, no good reason to believe that Babylon, in any form or sense whatever, covered at any time this large area.

On the other hand, the special ruins of Babil and Kasr and adjacent mounds seem to preserve both the name and the actual remains of Babylon (fig. 1). Here, on the left bank of the Euphrates, are vast city-walls, once five or six miles long.[13] They may be described roughly as enclosing half of a square bisected diagonally by the river, much as Herodotus writes; there is good reason to think that they had some smaller counterpart on the right bank, as yet scantily explored. Within these walls were the palaces of the Babylonian kings, Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar (625-561 B.C.), the temples of the national god Marduk or Merodach and other Babylonian deities, a broad straight road, Aiburschabu, running north and south from palaces to temples, a stately portal spanning this road at the Istar Gate, many private houses in the Merkes quarter, and an inner town-wall perhaps of earlier date. Street and gate were built or rebuilt by Nebuchadnezzar. He, as he declares in various inscriptions, 'paved the causeway with limestone flags for the procession of the Great Lord Marduk.' He made the Istar Gate 'with glazed brick and placed on its threshold colossal bronze bulls and ferocious serpent dragons'. Along the street thus built the statue of Marduk was borne in solemn march on the Babylonian New Year's Day, when the king paid yearly worship to the god of his country.[14]

FIG I.

BABYLON

Such are the remains of the city of Babylon, so far as they are known at present. They do not fit ill with the words of Herodotus. We can detect in them the semblance not indeed of one square but of two unequal half-squares, divided by the river; we can trace at least one great street parallel to the river and others which run at right angles to it towards the river. If the brick defences along the water-side have vanished, that may be due to their less substantial character and to the many changes of the river itself. To the student of Babylonian topography, the account of Herodotus is of very little worth. But it is as good as most modern travellers could compile, if they were let loose in a vast area of buildings, without plans, without instruments, and without any notion that a scientific description was expected of them.

The remains show also—and this is more to our purpose—the idea of the sacred processional avenue which recurs in fifth-century Greece—and is indeed beloved of architects in the most modern times. Here is a germ of town-planning. But whether this laying out of streets extended beyond the main highways, is less clear. The Merkes excavations occasionally show streets meeting at right angles and at least one roughly rectangular insula, of 150 x 333 ft. But the adjoining house-blocks agree neither in size nor shape, and no hint seems to have yet come to light of a true chess-board pattern.[15]

A little further evidence can be drawn from other Mesopotamian sites. The city of Asshur had a long, broad avenue like the sacred road of Babylon, but the one insula of its private houses which has yet been excavated, planned and published, shows no sign of rectangular planning.[16] There is also literary evidence that Sanherib (765-681 B.C.) laid out a 'Kingsway' 100 ft. wide to promote easy movement through his city of Nineveh, and Delitzsch has even credited the Sargonid dynasty generally (722-625 B.C.) with a care for the dwellings of common men as well as of gods and of kings.[17]

In conclusion, the mounds of Babil and Kasr and others near them seem to represent the Babylon alike of fact and of Herodotus. It was a smaller city than the Greek historian avers; its length and breadth were nearer four than fourteen miles. But it had at least one straight, ample, and far-stretching highway which gave space for the ceremonies and the processions, if not for the business or the domestic comforts, of life. In a sense at least, it was laid out with its streets straight. Nor was it the only city of such a kind in the Mesopotamian region. Asshur and Nineveh, both of them somewhat earlier in date than Babylon, possessed similar features. These towns, or at least Babylon, seem to have been known to Greek travellers, and probably suggested to them the adornment of their Hellenic homes with similar streets. The germ of Greek town-planning came from the east.

CHAPTER III

GREEK TOWN-PLANNING: FIRST EFFORTS

Greek town-planning began in the great age of Greece, the fifth century B.C. But that age had scant sympathy for such a movement, and its beginnings were crude and narrow. Before the middle of the century the use of the processional highway had established itself in Greece. Rather later, a real system of town-planning, based on streets that crossed at right angles, became known and practised. Later still, in the early fourth century, the growing care for town-life produced town by-laws and special magistrates to execute them. In some form or other, town-planning had now taken root in the Greek world.

The two chief cities of Greece failed, indeed, to welcome the new movement. Both Athens, the city which by itself means Greece to most of us, and Sparta, the rival of Athens, remained wholly untouched by it. Alike in the days of Themistocles and Pericles and in all its later history, Athens was an almost Oriental mixture of splendid public buildings with mean and ill-grouped houses. An often-quoted saying of Demosthenes puts the matter in its most favourable light:

'The great men of old built splendid edifices for the use of the State, and set up noble works of art which later ages can never match. But in private life they were severe and simple, and the dwelling of an Aristides or a Miltiades was no more sumptuous than that of any ordinary Athenian citizen' (Third Olynthiac Oration, 25).

This is that 'desire for beauty and economy' which Pericles (or Thucydides) praised in the Funeral Oration. It has a less lovely side. Not a few passages in Greek literature speak, more or less clearly, of the streets of Athens as narrow and tortuous, unpaved, unlighted, and more like a chaos of mud and sewage than even the usual Greek road. Sparta was worse. There neither public nor private buildings were admirable, and the historian Thucydides turned aside to note the meanness of the town.

Nevertheless, the art of town-planning in Greece probably began in Athens. The architect to whom ancient writers ascribe the first step, Hippodamus of Miletus,—born about or before 480 B.C.,—seems to have worked in Athens and in connexion with Athenian cities, under the auspices of Pericles. The exact nature of his theories has not been recorded by any of the Greek writers who name him. Aristotle, however, states that he introduced the principle of straight wide streets, and that he, first of all architects, made provision for the proper grouping of dwelling-houses and also paid special heed to the combination of the different parts of a town in a harmonious whole, centred round the market-place. But there seems to be no evidence for the statement sometimes made, that he had any particular liking for either a circular or a semicircular, fan-shaped town-plan.

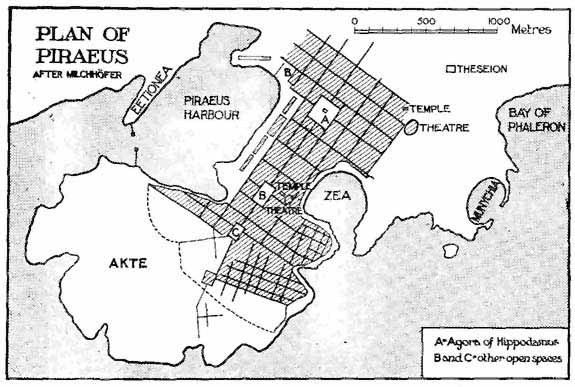

Piraeus (fig. 2).

Three cities are named as laid out by Hippodamus. Aristotle tells us that he planned the Piraeus, the port of Athens, with broad straight streets. He does not add the precise relation of these streets to one another. If, however, the results of recent German inquiries and conjectures are correct, and if they show us his work and not—as is unfortunately very possible—the work of some later man, his design included streets running parallel or at right angles to one another and rectangular blocks of houses; the longer and presumably the more important streets ran parallel to the shore, while shorter streets ran at right angles to them down to the quays. Here is a rectangular scheme of streets, though the outline of the whole town is necessarily not rectangular (fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

PLAN OF PIRAEUS

Thurii.

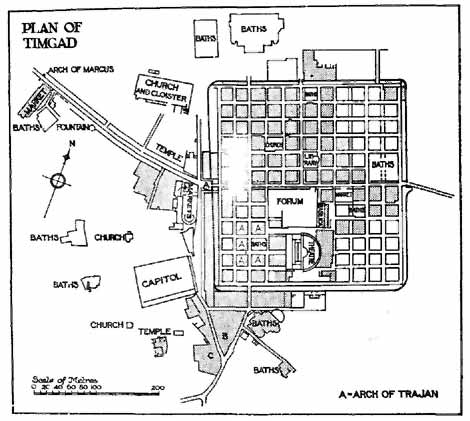

Another town ascribed to Hippodamus is the colony which the Athenians and others planted in 443 B.C. at Thurii in southern Italy, of which Herodotus himself is said to have been one of the original colonists. Its site has never been excavated, and indeed one might doubt whether excavation would show the street plan of 443 B.C. or that of a later and possibly even of a Roman age, when the town was recolonized on the Roman system. But the historian Diodorus, writing in the first century B.C. and no doubt embodying much older matter, records a pertinent detail. The town, he says, was divided lengthways by four streets and crossways by three. Plainly, therefore, it had a definite and rectangular street-planning, though the brevity of the historian does not enable us to decide how many house-blocks it had and how far the lesser streets were symmetrical with these seven principal thoroughfares. In most of the cases which we shall meet in the following sections of this treatise, the number of streets running-straight or at right angles is very much greater than the number assigned to Thurii. I may refer for example to the plans of Priene, Miletus, and Timgad.

Rhodes.

A third city assigned to Hippodamus is Rhodes. This, according to Strabo, was laid out by 'the architect of the Piraeus'; according to others, it was built round its harbour like the seats of an ancient theatre round the orchestra, that is, fan-fashion like Karlsruhe. However, this case is doubtful. Rhodes was laid out in 408 B.C., thirty-five years after the planting of Thurii and seventy years after the approximate date of the birth of Hippodamus. It is conceivable but not altogether probable that Hippodamus was still planning towns in his extreme old age, nor is it, on political grounds, very likely that he would be planning in Rhodes. As, however, we do not know the real date of his birth, and as Strabo does not specifically mention his name, certainty is unattainable.[18]

If we cannot tell exactly how Hippodamus planned cities or exactly which he planned, still less do we know how far town-planning on his or on any theory came into general use in his lifetime or indeed before the middle of the fourth century. Few Greek cities have been systematically uncovered, even in part. Fewer still have revealed street-planning which can be dated previous to that time. It does not follow, when we find streets in the ruins of an ancient city, that they must belong to its earliest period. That is not true of towns in any age, modern or mediaeval, Roman or Greek. Some Greek cities were founded in early times, were rebuilt in the Macedonian period, and again rebuilt in the Roman period. Without minute excavation it may be impossible to assign the town-plan of such a place to its proper place among these three periods.

We have, however, at Selinus in Sicily and Cyrene on the north coast of Africa, two cases which may belong to the age of Hippodamus. They are worth describing, since they illustrate both the difficulty of reaching quite certain conclusions and also the system which probably did obtain in the later fifth and the early fourth century.

Selinus (fig. 3).

At Selinus the Italian archaeologists discovered some years ago, in the so-called Acropolis, a town of irregular, rudely pear-shaped outline with a distinct though not yet fully excavated town-plan. Two main thoroughfares ran straight from end to end and crossed at right angles (fig. 3), the longer of these thoroughfares being just a quarter of a mile long and 30 ft. wide. From these two main streets other narrower streets (12-18 ft. wide) ran off at right angles; the result, though not chess-board pattern, is a rectangular town-plan. Unfortunately, it cannot be dated. Selinus was founded in 648 B.C., was destroyed in 409, then reoccupied and rebuilt, and finally destroyed for ever in 249. Its town-planning, therefore, might be as early as the seventh century B.C. Or (and this is the most probable conclusion) it may date from the days of Selinuntine prosperity just before 409, when the city was growing and the great Temple of Zeus or Apollo was rising on its eastern hill. Or again, though less probably, it may have been introduced after 400. We may conclude that we have here a clear case of town-planning and we may best refer it to the later part of the fifth century.[19]

FIG. 3.

PLAN OF SELINUS

Cyrene (fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

PLAN OF CYRENE

At Cyrene the researches of two English archaeologists about 1860 disclosed a town-plan based, like that of Selinus, on two main streets which crossed at right angles (fig. 4). Here, however, the other streets do not seem to have been planned uniformly at right angles to the two main thoroughfares, and the rectangular scheme is therefore less complete and definite than at Selinus. Cyrene, unfortunately, resembles Selinus in another respect, that we have no proper knowledge of the date when its main streets were laid out. It was founded somewhere in the seventh century B.C. and Pindar, in an ode written about 466 B.C., mentions a great processional highway there. Whether this was one of the two roads above mentioned is not clear. But it is not probable, since Pindar's road seems hardly to have been inside the city at all.[20]

In these two cases and in one or two others which might be noted from the same or later times, the town-scheme includes rectangular elements without any strict resemblance to the chess-board pattern. The dominant feature is the long straight street, of great width and splendour, which served less as the main artery of a town than as a frontage for great buildings and a route for solemn processions. Here, almost as in Babylon, we have the spectacular element which architects love, but which is, in itself, insufficient for the proper disposition of a town. Long and ample streets, such as those in question, might easily be combined, as indeed they are combined in some modern towns of southern Europe and Asia, with squalid and ill-grouped dwelling-houses. Hippodamus himself aimed at something much better, as Aristotle tells us. But it was not till after 350 B.C. or some approximate date, that dwelling-houses were actually arranged and grouped on a definite system.[21]

FIG. 5.

SOLUNTUM

It was probably, however, in the first half of the fourth century that the Greek cities began to pass by-laws relating to the police, the scavenging and the general public order of their markets and streets, and to establish Agoranomi to control the markets and Astynomi to control the streets. These officials first appear in inscriptions after 350, but are mentioned in literature somewhat earlier. An account of the Athenian constitution, ascribed formerly to Xenophon and written (as is now generally agreed) about 430-424 B.C., mentions briefly the prosecution of those who built on to the public land, that is (apparently), who encroached upon the streets. But it is silent as to specific officers, Astynomi or other. Plato, however, in his 'Laws', which must date a little earlier than his death in 347, alludes on several occasions to such officers. They were to look after the private houses 'in order that they may all be built according to laws', and to police and clean the roads and water-channels, both inside and outside of the city. A prohibition of balconies leaning over the public streets, and of verandas projecting into them, is also mentioned in two or three writers of the fourth century and is said to go back to a much earlier date, though its antiquity was probably exaggerated.[22]

The municipal by-laws which these passages suggest clearly came into use before, though perhaps not long before, the middle of the fourth century. They do not directly concern town-planning; they involve building regulations only as one among many subjects, and those regulations are such as might be, and in many cases have been, adopted where town-planning was unknown. But they are natural forerunners of an interest in town-planning. As in modern England, so in fourth-century Greece, their appearance suggests the growth of a care for well-ordered town life and for municipal well-being which leads directly to a more elaborate and methodical oversight of the town as an organized combination of houses and groups of houses.

As we part from this early Greek town-planning, we must admit that altogether we know little of it. There was such a thing: among its main features was a care for stately avenues: its chief architect was Hippodamus. Thus much is clear. But save in so far as Milchhöfer's plans reproduce the Piraeus of B.C. 450 or 400, we cannot discern either the shape or the size of the house-blocks, or the grouping adopted for any of the ordinary buildings, or the scheme of the ordinary roads. We may even wonder whether such things were of much account in the town-planning of that period.

CHAPTER IV

GREEK TOWN-PLANNING: THE MACEDONIAN AGE, 330-130 B.C.

The Macedonian age brought with it, if not a new, at least a more systematic, method of town-planning. That was the age when Alexander and his Macedonian army conquered the East and his successors for several generations ruled over western Asia, when Macedonians and Greeks alike flocked into the newly-opened world and Graeco-Macedonian cities were planted in bewildering numbers throughout its length and breadth. Most of these cities sprang up full-grown; not seldom their first citizens were the discharged Macedonian soldiery of the armies of Alexander and his successors. The map of Turkey in Asia is full of them. They are easily recognized by their names, which were often taken from those of Alexander and his generals and successors, their wives, daughters, and relatives. Thus, one of Alexander's youngest generals, afterwards Seleucus I, sometimes styled Nicator, founded several towns called Seleucia, at least three called Apamea, and others named Laodicea and Antiochia, thereby recording himself, his Iranian wife Apama, his mother Laodice and his father Antiochus, and his successors seem to have added other towns bearing the same name. Indeed, two-thirds of the town-names which are prominent in the later history of Asia Minor and Syria, date from the age of Alexander and his Macedonians.

Many discoveries show that these towns were laid out with a regular 'chess-board' street-plan. That method of town-planning now made definite entry into the European world. No architect or statesman is recorded to have invented or systematically encouraged it. Alexander himself and his architect, one Dinocrates of Rhodes or perhaps of Macedonia, seem to have employed it at Alexandria in Egypt, and this may have set the fashion. Seven years after Alexander's death it recurs at Nicaea in Bithynia, which was refounded by one of Alexander's successors in 323 B.C. and was laid out on this fashion. But no ancient writer credits either the founder or the architect of Alexandria or the founder of Nicaea with any particular theory on the subject. If the chess-board fashion becomes now, with seeming suddenness, the common—although not the universal—rule, that is probably the outcome of the developments sketched in the last chapter. Approximations to chess-board planning had been here and there employed in the century before Alexander. When his conquests and their complicated sequel led, amongst other results, to the foundation of many new towns, it was natural that the most definite form of planning should be chosen for general use.

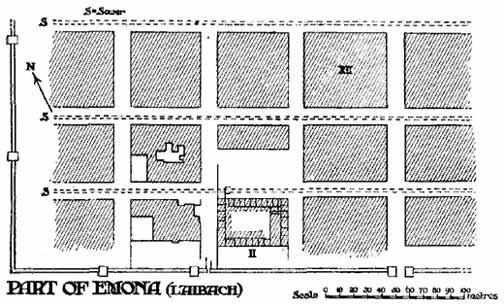

We might, however, wonder whether its adoption was helped by the military character of the generals who founded, and the discharged soldiers who formed the first inhabitants of so many among these towns. Military men are seldom averse to rigidity. It is worth noting, in this connexion, that when chess-board planning came into common use in the Roman Empire, many—perhaps most—of the towns to which it was applied were 'coloniae' manned by time-expired soldiers. So, too, in the Middle Ages and even in comparatively modern times, the towns laid out with rectangular street-plans in northern Italy, in Provence, in the Rhine Valley, are for the most part due in some way or other to military needs.[23] In our own days rectangular planning is a dominant feature of the largest and newest industrial towns. They are adapting a military device to the purposes of an industrial age.

Priene (figs. 6-8).

The best instance of the new system is not perhaps the most famous. Priene was a little town on the east coast of the Aegean. The high ridge of Mycale towered above it; Miletus faced it across an estuary; Samos stood out seawards to the west. In its first dim days it had been perched on a crag that juts out from the overhanging mountain; there its life began, we hardly know when, in the dawn of Greek history. But it had been worn down in the fifth century between the upper and the nether millstone of the rival powers of Samos and Miletus. Early in the Macedonian age it was refounded. The old Acropolis was given up. Instead, a broad sloping terrace, or more exactly a series of terraces, nearer the foot of the hill, was laid out with public buildings—Agora, Theatre, Stoa, Gymnasium, Temples, and so forth—and with private houses. The whole covered an area of about 750 yds. in length and 500 yds. in width. Priene was, therefore, about half the size of Pompeii (p. 63). It had, as its excavators calculate, about 400 individual dwelling-houses and a population possibly to be reckoned at 4,000.

FIG. 6.

GENERAL OUTLINE OF PRIENE

A, B, C. Gates. D, E, F, H, M, P. Temples (see fig. 7). G. Agora, Market. I.

Council House, K. Prytaneion. L, Q. Gymnasium. N. Theatre, O. Water-reservoir,

R. Race-course.

FIG. 7.

PART OF PRIENE AS EXCAVATED 1895-8

(From the large plan by Wiegand and Schrader.)

FIG. 8.

PRIENE, PANORAMA OF THE TOWN

(As restored by Zippelius.)

In the centre was the Agora or market-place, with a temple and other large buildings facing on to it; round them were other public buildings and some eighty blocks of private houses, each block measuring on an average 40 x 50 yds. and containing four or five houses. The broader streets, rarely more than 23 ft. wide, ran level along the terraces and parallel to one another. Other narrower streets, generally about 10 ft. wide, ran at right angles up the slopes, with steps like those of the older Scarborough or of Assisi.[24] The whole area has not yet been explored and we do not know whether the houses were smaller or larger, richer or poorer, in one quarter than in another, but the regularity of the street-plan certainly extended over the whole site.

Despite this reasoned and systematic arrangement, no striking artistic effects appear to have been attempted. No streets give vistas of stately buildings. No squares, save that of the Agora—120 by 230 ft. within an encircling colonnade—provide open spaces where larger buildings might be grouped and properly seen. Open spaces, indeed, such as we meet, in mediaeval and Renaissance Italy or in modern English towns of eighteenth century construction, were very rare in Priene. Gardens, too, must have been almost entirely absent. In the area as yet uncovered, scarcely a single dwelling-house possessed any garden ground or yard.[25]

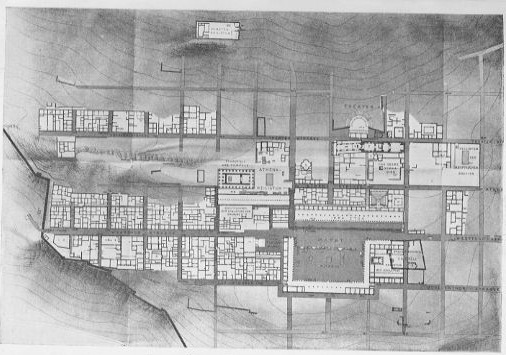

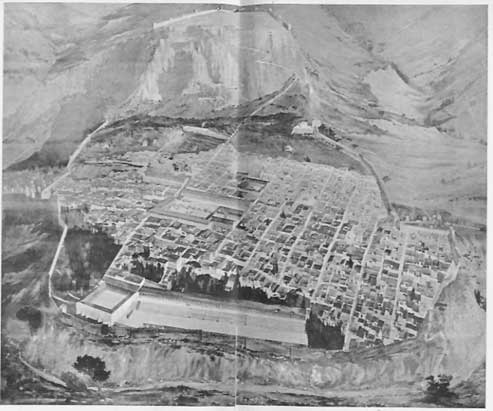

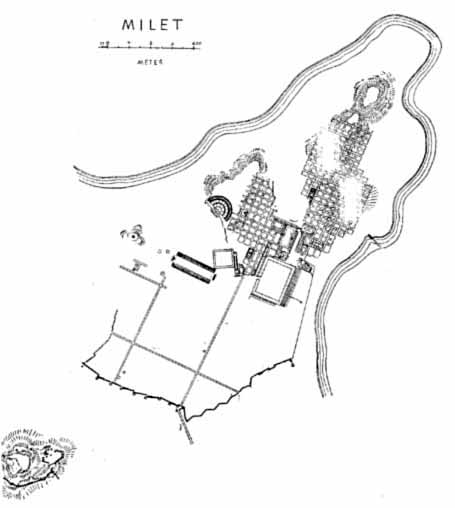

Miletus (fig. 9).

The skill of German archaeologists has revealed what town-planning meant in a small town rebuilt in the Alexandrine period. No other even approximately complete example has been as yet uncovered on any other site. But spade-work at the neighbouring and more famous city of Miletus has uncovered similar street-planning there. In one quarter, the only one yet fully excavated, the streets crossed at right angles and enclosed regular blocks of dwelling-houses measuring 32 x 60 yds. (according to the excavators) but sub-divided into blocks of about 32 yds. square (fig. 9). These blocks differ somewhat in shape from those of Priene, which are more nearly square; whether they differ in date is more doubtful. They are certainly not earlier than the Macedonian era, and one German archaeologist places the building or rebuilding of this quarter of Miletus after that of Priene and in a 'late Hellenistic' and apparently Roman period. There is unquestionably much Roman work in Miletus; there seems, however, no sufficient reason for ascribing the house-blocks shown on fig. 7 to any date but some part of the Macedonian period. Though differently shaped, they do not differ very greatly in actual area from those of Priene. They are somewhat smaller, but only by about 60 sq. yds. in each average-sized plot.[26]

FIG. 9.

MILETUS, AS EXCAVATED BY WIEGAND

(Archãologischer Anzeiger, 1911, p. 421.)

Alexandria.

A yet more famous town, founded by Alexander himself, is definitely recorded by ancient writers to have been laid out in the same quasi-chess-board fashion, with one long highway, the Canopic Street, running through it from end to end for something like four miles.[27] Unfortunately the details of the plan are not known with any certainty. Excavations were conducted at the instigation of Napoleon III in 1866 by an Arab archaeologist, Mahmud Bey el Fallaki, and, according to him, showed a regular and rectangular scheme in which seven streets ran east and west while thirteen ran north and south at right angles to them. The house-blocks divided by these streets were thought to vary somewhat in size but to measure in general about 300 x 330 metres.[28] More recent research, however, has not confirmed Mahmud's plans. The excavations of Mr. Hogarth and M. Botti suggest that many of his lines are wrong and that even his Canopic Street is incorrectly laid down. Mr. Hogarth, indeed, concludes that 'it is hopeless now to sift his work; those who would treat the site of Alexandria scientifically must ignore him and start de novo'. More recent excavation, carried out by Dr. Noack in 1898-9, seemed to show that the ancient streets which can now be traced beneath Alexandria belong to a Roman age, though they may of course follow older lines, and that, if some items in Mahmud's plans are possibly right, the errors and omissions are serious. We may accept as certain the statement that Alexandria was laid out with a rectangular town-plan; we cannot safely assume that Mahmud has given a faithful picture of it.[29]

Nicaea.

Priene, Miletus, and Alexandria supply more or less well-known instances of Macedonian town-planning. They can be reinforced by a crowd of less famous examples, attested by literature or by actual remains. One of the most characteristic is known to us from literature, Nicaea in Bithynia, founded by one of the Macedonians in 316 B.C. and renamed by another some years later in honour of his wife Nicaea. Strabo, writing about A.D. 15, describes it and his description no doubt refers to arrangements older than the Romans. It formed, he says, a perfect square in which each side measured four stades, a little over 800 yds. In each side—apparently in the middle of each side—there was one gate, and the streets within the walls were laid out at right angles to one another. A man who stood at a certain spot in the middle of the Gymnasium could see straight to all the four gates.[30] Here is the chess-board pattern in definite form, though the central portion of the city may have been laid out under the influence of spectacular effect rather than of geometry.

Sicyon, Thebes, &c.

Another Macedonian town-plan may be found at Sicyon, a little west of Corinth. This old Greek city was rebuilt by Demetrius Poliorcetes about 300 B.C., and is described by a Greek writer of the first century B.C. as possessing a regular plan and roads crossing at right angles. The actual remains of the site, explored in part by English and French archaeologists early in the nineteenth century, show some streets which run with mathematical straightness from north-east to south-west and others which run from north-west to south-east.[31] These streets might, indeed, date from the period when Sicyon was the chief town of the Roman province of Achaia, the period (that is) between the overthrow of Corinth in 146 B.C. and its restoration just a century later. But that was not an epoch when such rebuilding is likely to have been carried through. Friendly as the Republican government of Rome showed itself in other ways to Hellas, there is no reason to think that it spent money on town-planning in Hellenic cities. It is far more probable that the town-plan of Sicyon dates from the Macedonians.

To the same Macedonian epoch we may perhaps ascribe the building or rather the rebuilding of Boeotian Thebes, which one who passes for a contemporary writer under the name of Dicaearchus, describes as 'recently divided up into straight streets'.[32] To the same period Strabo definitely assigns the newer town of Smyrna, lying in the plain close to the harbour. It was due, he says, to the labours of the Macedonians, Antigonus, and Lysimachus.[33] We may perhaps assign to the same period the town-planning of Mitylene in Lesbos, which Vitruvius mentions as so splendid and so unhealthy, were it not that his explanation of its unhealthiness suggests rather a fan-shaped outline than a square. It was, he says, intolerable, whatever wind might blow. With a south wind, the wind of damp and rain, every one was ill. With a north-west wind, every one coughed. With a north wind, no one could stand out of doors for the chilliness of its blasts.[34] Streets that lay open to the north and the north-west and the south, equally and alike, could only be found in a town-plan fashioned like a fan. But perhaps Vitruvius only selected three of the plagues of Lesbos.

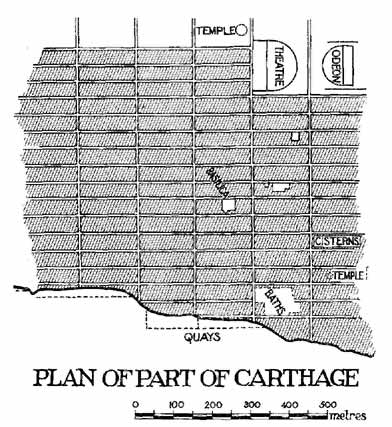

In other cases the same planning was probably adopted, although the evidence as yet known shows only a rectangular plan of main streets, such as we have met in Pre-Macedonian Greece. In Macedonia itself, Thessalonika, laid out perhaps about 315 B.C., had at least one main street running southwards to the sea and two more running east and west at right angles to that.[35] In Asia two Syrian towns, which occupy sites closed to Hellenic culture before Alexander, may serve as examples. Apamea on the Orontes was built by the Macedonians, rose forthwith to importance, and retained its vigorous prosperity through the Roman Empire; in A.D. 6 it was 'numbered' by Sulpicius Quirinius, then the governor of Syria, and the census showed as many as 117,000 citizens settled in the city and its adjacent 'territory'. Its ruins seem to be mainly earlier than the Romans, and its streets may well date from its Macedonian founders. In outline it is an irregular oblong, nearly an English mile in length and varying in width from half to two-thirds of a mile. A broad and straight street, lined throughout with colonnades, runs from end to end of its length and passes at least five great buildings, which seem to be the temples and palaces of the Seleucid kings. Two other streets cross this main street at right angles. Whether the smaller thoroughfares took the same lines can be determined only by excavation. It would be a gentle guess to think so.[36]

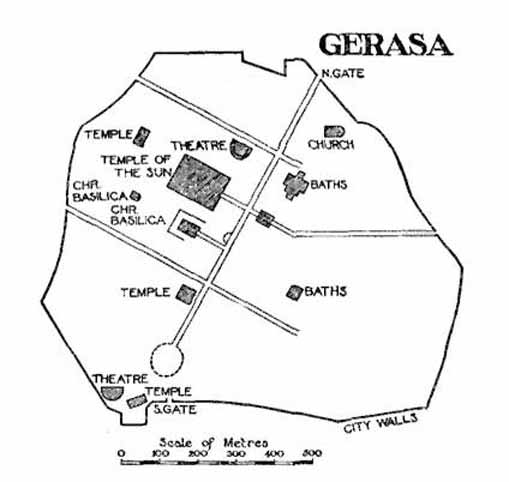

Further south, on the edge of the Haurân, stood the town of Gerasa. This too, like Apamea, was built by the Macedonians and flourished not only in their days but during the following Roman age. Its general outline was ovoid, its greatest diameter three quarters of a mile, its area some 235 acres—nearly the same with Roman Cologne and Roman Cirencester. Its streets resembled those of Apamea. A colonnaded highway ran straight through from north to south; two other streets crossed at right angles, and its chief public buildings, the Temple of the Sun and three other temples, two theatres and two public baths, stood near these three streets (fig. 10). Again the evidence proves rectangular town-planning in broad outline; excavation alone can tell the rest.[37]

FIG. 10.

GERASA

In the towns just described a distinctive feature is the 'chess-board' pattern of streets and rectangular house-blocks. That, of course, is the feature which most concerns us here. It may not have looked so predominant to their builders and inhabitants. The towns which the Macedonians founded were not seldom rich and large; several were the capitals of powerful and despotic rulers. In such towns we expect great public buildings, temples, palaces. It is not surprising if sometimes those who reared them cared solely for the spectacular grouping of magnificent structures and forgot the private houses and the general plan of the town.

Pergamum.

One such instance from the Macedonian age, perhaps the most instructive which we could ever hope to get,[38] is Pergamum, in the north-west of Asia Minor. This has been thoroughly explored by German science; its remains are superb; its chief buildings date from an age when town-planning had grown familiar to the Greek world. About 300 B.C. it was a hill-town where a Macedonian chief could bestow a war-chest. It grew both populous and splendid in the third and second centuries B.C. under the Attalid kings; later builders, Augustus or Trajan or other, added little either to its general design or to its architectural glory. The dominant idea was that of a semi-circle of great edifices, crowning the crest and inner slopes of a high crescent-shaped ridge. Near the northern and highest end of this ridge stood the palace of the Attalid princes, afterwards buried beneath a temple in honour of Trajan. Next, to the south, was the Library—with stores of papyri worth more perhaps to the world than all the architecture of Pergamon. The middle of the crescent held the shrine of Athena, goddess of Pergamon, and beside it the Altar of Zeus the Saviour, gigantic in size, splendid with sculpture, itself the equal of an Acropolis. Lastly, the southern or lower end of the ridge bore a temple of Dionysus and an Agora for Assemblies.

These buildings ringed the hill-top in stately semi-circle; below them, a theatre was hewn out of the slopes and a terrace 250 yds. long was held up by buttresses against precipitous cliffs. Lower yet, beneath the Agora, the town of common men covered the lower hill-side in such order or disorder as its steepness allowed. Here was no conventional town-planning. Only a yet lower and later city, built in Roman days on more or less level spaces beside the stream Selinus, seems perhaps to have been laid out in chess-board fashion.[39] The Attalid kings, the founders of Pergamon, cared only for splendid buildings splendidly adorned. If their abrupt hill-side forbade the straight and broad processional avenues of some other Greek cities, they crowned their summits instead with a crescent of temples and palaces which had not its like on the shores of the Aegean.

Yet even Pergamon had its building-laws and by-laws for the protection of common life. A Pergamene inscription contains part of a 'Royal Law' which apparently dates from one of the Attalid rulers. It is imperfect. But we can recognize some of the items for which it provided. Houses which fell or threatened to fall on to the public street, or which otherwise became ruinous, could be dealt with by the Astynomi; if their owners failed to repair them, these magistrates were to make good the defects themselves and to recover the cost, and a fine over and above it, from the owners; if the Astynomi neglected their duty, the higher magistrates, the Strategi, were to take up the matter. Streets were to be cleaned and scavenged by the same Astynomi. Brick-fields were expressly forbidden within the city. The widths of roads outside the town were fixed and owners of adjacent land were held liable for their repair, and there was possibly some similar rule, not preserved on the inscription, for roads inside the walls; at Priene, it seems, these latter were in the care of the municipality. There were provisions, too, for the repair of common walls which divided houses belonging to two owners, and also for the prevention of damp where two houses stood side by side on a slope and the wall of the lower house stood against the soil beneath the upper house.[40]

These rules are very like those which were coming into use before 330 B.C. (p. 37). Only, they are more elaborate, and it is significant that the inscriptions begin in Macedonian and later days to give more and fuller details as to the character of these laws and as to the existence in many cities of officials to execute them. It is not surprising to find that Roman legislation of the time of Caesar and the early Empire applies these or very similar rules to the local government of the Roman municipalities of the Empire (p. 137).

So common in the Macedonian world was the town-planning which has been described above, that the literature of the period, even in its casual phrases and incidental similes, speaks of towns as being normally planned in this fashion. Two examples from two very different authors will suffice as illustration. Polybius, writing somewhere about B.C. 150, described in well-known chapters the scheme of the Roman camp, and he concludes much as follows: 'This being so, the whole outline of the camp may be summed up as right-angled and four-sided and equal-sided, while the details of its street-planning and its general arrangement are precisely parallel to those of a city' (VI. 31, 10). He was comparing the Greek town, as he knew it in his own country, with the encampment of the Roman army; he found in the town the aptest and simplest parallel which he could put before his readers. A much later writer, living in a very different environment and concerned with a very different subject, fell nevertheless under the influence of the same ideas. Despite his 'sombre scorn' for things Greek and Roman, St. John, when he wished to figure the Holy City Jerusalem, centre of the New Heaven and New Earth, pictured it as a city lying foursquare, the length as large as the breadth, and entered by twelve gates, 'on the east three gates, on the north three gates, on the south three gates, and on the west three gates.'[41]

The instances and items cited in the preceding paragraphs lie within the limits of the Greek world and of the Roman Empire. We might perhaps wish to pursue our speculations and ask whether this vigorous system influenced foreign lands, and whether the Macedonian army carried the town-plan of their age, in more or less perfect form, as far as their conquests reached. Alexander settled many soldiers in lands which were to form his eastern and north-eastern frontiers, as if against the central-asiatic nomads. Merv and Herat, Khokand and Kandahar,[42] have been thought—and, it seems, thought with some reason—to date from the Macedonian age and in their first period to have borne the name Alexandria. But no Aurel Stein has as yet uncovered their ruins, and speculation about them is mere speculation.

CHAPTER V

ITALIAN TOWN-PLANNING. THE ORIGINS

If Greek and Macedonian town-planning are fairly well known, the Roman Empire offers a yet larger mass of certain facts, both in Italy and in the provinces. The beginnings, naturally, are veiled in obscurity. We can trace the system in full work at the outset of the Empire; we cannot trace the steps by which it grew. Evidences of something that resembles town-planning on a rectangular scheme can be noted in two or three corners of early Italian history—first in the prehistoric Bronze Age, then in a very much later Etruscan town, and thirdly on one or two sites of middle Italy connected with the third or fourth century B.C. These evidences are scanty and in part uncertain, and their bearing on our problem is not always clear, but they claim a place in an account of Italian town-planning. To them must be added, fourthly, the important evidence which points to the use of a system closely akin to town-planning in early Rome itself.

The Terremare (fig. 11).

(i) We begin in the Bronze Age, somewhere between 1400 and 800 B.C., amidst the so-called Terremare. More than a hundred of these strange settlements have been examined by Pigorini, Chierici, and other competent Italians. Most of them occur in a well-defined district between the Po and the Apennines, with Piacenza at its west end and Bologna at its east end. Some have also been noted on the north bank of the Po near Mantua, both east and west of the Mincio, and two or three elsewhere in Italy. Archaeologically, they all belong to the Bronze Age; they seem, further, to be the work of a race distinct from any previous dwellers in North Italy, which had probably just moved south from the Danubian plains. At some time or other this race had dwelt in lake-villages. They were now settled on dry ground and far away from lakes—one of their hamlets is high in the Apennines, nearly 1,900 ft. above the sea. But they still kept in the Terremare the lacustrine fashion of their former homes.

The nature of these strange villages can best be explained by an account of the best-known and the largest example of them (fig. 11). At Castellazzo di Fontanellato, a little west of Parma, are the vestiges of a settlement which, with its defences, covered an area of about forty-three acres. In outline it was four-sided; its east and west sides were parallel to one another, and the whole resembled a rectangle which had been pulled a trifle askew. Round it ran a solid earthen rampart, 50 ft. broad at the base and strengthened with woodwork (plan, B). In front of the rampart was a wet ditch (A), 100 ft. wide, fed with fresh water from a neighbouring brook by an inlet at the south-western corner (C) and emptied by an outfall on the east (D). One wooden bridge gave access to this artificial island at its southern end (E). The area within the rampart, a little less than thirty acres in extent, was divided into four parts by two main streets, which would have intersected at right angles had the place been strictly rectangular; other narrower streets ran parallel to these main thoroughfares. On the east side (F) was a small 'citadel'—arx or templum—with ditch, rampart and bridge of its own (G, H); in this were a trench and some pits (K) which seemed by their contents to be connected with ritual and religion. Outside the whole (L, M) were two cemeteries, platforms of urns set curiously like the village itself, and also a little burning ghat.[43] The population of the village is necessarily doubtful. A German writer, Nissen, has reckoned it at four or five thousand, men, women and children together, crowded into small huts. But this estimate may be too high. In any case, many of the Terremare are much smaller.

FIG. 11.

TERRAMARA OF CASTELLAZZO DI FONTANELLATO

These Terremare bear a strong likeness to the later Italian town-planning, and they are usually taken to be the oldest discoverable traces of that system. This means that the Italian town-planning was derived from other sources besides Greece or the East, since the Terremare are far older than Hippodamus or even Nebuchadnezzar and Sennacherib (pp. 23, 29). It must be added that our present knowledge does not allow us to follow the actual development of the Terremare into historic times, and to link them closely with the later civilization of Central Italy. When some modern scholars call the men of the Terremare by the name 'Italici', they express a hope rather than a proven fact. It may be safer, for the moment, to avoid that name and to refrain from theories as to the exact relation between prehistoric and historic. But we shall see below that the existence of a relation between the two is highly probable.

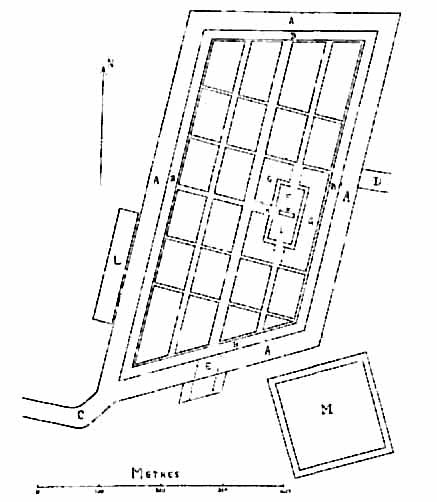

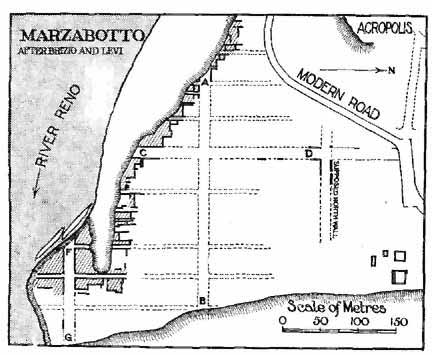

Marzabotto (fig. 12).

FIG. 12.

MARZABOTTO

(AB, FG, CD, main streets. The shading represents excavated houses.)

(ii) A greater puzzle, dating probably from the fifth century B.C., meets us in the ruins of a nameless little Etruscan town which stood outside of Etruria proper, on the north slopes of the Apennines. Its site is fifteen miles south of Bologna, close to the modern Marzabotto, on the left bank of the little river Reno. Only a tiny part has been uncovered. But the excavators have not hesitated to complete their results conjecturally into a rectangular town-plan, with streets crossing at right angles and oblong blocks of houses measuring from 158 to 176 yds. in length and 37 or 44 or 71 yds. in width (fig. 12). The whole must have been laid out at once, and the smaller remains seem to show that this was done by Etruscans. In the fourth century the place was sacked by the Gauls, and though there was later occupation,[44] its extent is doubtful.[45]

Further excavation is, however, needed to confirm this generally accepted interpretation of the place. Nothing has been noted elsewhere in Etruria or its confines to connect the Etruscans with any rectangular form of town-plan. At Veii, for example, most of the Etruscan city has lain desolate and unoccupied ever since the Romans destroyed it, but the site shows no vestige of streets crossing at right angles or of oblong blocks of houses. At Vetulonia the excavated fragment of an Etruscan city shows only curving and irregular streets.[46] Nor is there real reason to believe that the 'Etruscan teaching' learnt by Rome included an art of town-planning (p. 71) or that, as a recent French writer has conjectured, the Etruscans brought any such art with them from the East and communicated it to the West. We must conclude that at Marzabotto we have a piece of evidence which we cannot set into its proper historical framework. We might perhaps call it an early blend of Greek and Italian methods and compare it with Naples (p. 100). It is odd that four out of seven house-blocks should measure just under 120 Roman ft. in width and thus approximate to a figure which we meet often elsewhere in the Roman world (p. 79). But it would be well to learn more of the plan by further excavation.

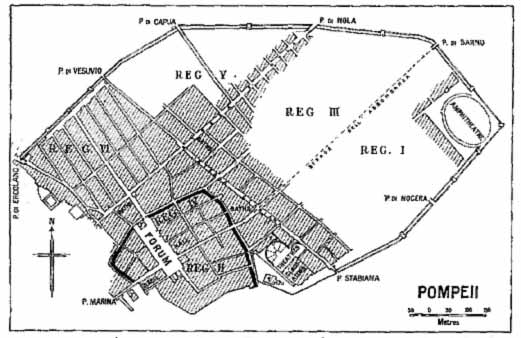

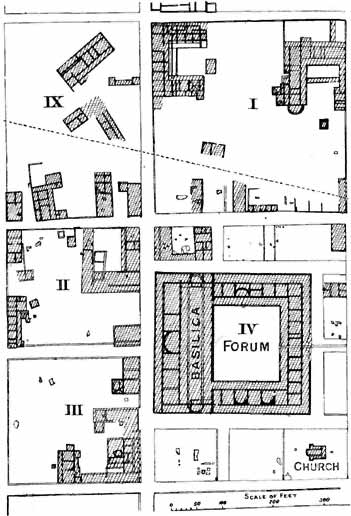

Pompeii (fig. 13).

(iii) A third piece of evidence can be found on a site which historians and novelists alike connect mainly with the Roman Empire, but which dates back to the days of the early or middle Republic. Pompeii began in or before the sixth century B.C. as an Oscan city. For a while, we hardly know when, it was ruled by Etruscans. Later, about 420 B.C., it was occupied by Samnites. Finally, it became Roman; it was refounded in 80 B.C. as a 'colonia' and repeopled by soldiers discharged from the armies of Sulla. In A.D. 79 it reached its end in the disaster to which it owes its fame. Its life, therefore, was long and full of destruction, re-building, enlargement. Its architectural history is naturally hard to follow. Many of its buildings, however, can be dated more or less roughly by the style of their ornament or the character of their material, and the lines of its streets suggest some conjectures as to its growth which deserve to be stated even though they may conflict with the received opinions about Pompeii. It will be understood, of course, that these conjectures, like all speculations on Pompeii, are limited by the fact that barely half of its area has been as yet uncovered, and that very little search has been made beneath the floors and pavements of its latest period.[47]

FIG. 13.

POMPEII

(T = Temple. The area of the supposed original settlement is outlined in black.)

As we know it at present, Pompeii is an irregular oval area of about 160 acres, planted on a small natural hill and girt with a stone wall nearly two miles in circumference (fig. 13). On the west there was originally access to the sea, and on this side the walls have disappeared or have not been yet uncovered. Near this end of the town is the Forum, with the principal temples and public buildings round it. At the east end of the town, nearly 1200 yds. from the western extremity, is the amphitheatre, and the town-walls appear to have been drawn so as to include it. Two main streets, now called the Strada di Nola and the Strada dell' Abbondanza, cross the town from SW. to NE. The main streets from NW. to SE. are less distinct, but the Strada Stabiana certainly ran from wall to wall. While there is some appearance of symmetry in the streets generally, it does not go very far; there is hardly a right angle, or any close approach to a right angle, at any street corner.

It is generally held, as Mau has argued, that the whole town was laid out at once, perhaps during the Etruscan period, on one plan of streets crossing at right angles. Two principal streets, those now styled the Strada di Mercurio and the Strada di Nola, are considered to be the main streets of this earliest town-plan, and to give it its general direction. A third main street, the Strada Stabiana, which cuts obliquely across from the Vesuvian to the Stabian Gate and mars the supposed symmetry of this town-plan, is ascribed to the influence of a small natural depression along which it runs, while a small area east of the Forum, which also breaks loose from the general scheme, is thought to have been laid out abnormally in order to remedy the effect of this obliquity.[48]

This theory is open to objections. In the first place the streets (even apart from those just east of the Forum) do not really form one symmetrical plan. Region VI fits very ill with Regions I and III. Both indicate systematic planning. But Region VI is laid out in oblong blocks 110 ft. wide and either 310 ft. or 480 ft. long, while Regions I and III are made up of approximately square blocks about 200 ft. each way. Moreover, the orientation of the blocks is different. Those in Region VI follow the lines of the Strada di Mercurio; those of Regions I and II, and perhaps also of Region V, are dominated by the Strada Stabiana. Yet there is no obvious reason why this difference should not have been avoided; it results, indeed, in awkward corners and inconvenient spaces. Nor, again, can we accept as in any degree adequate the cause assigned by Mau for the odd orientation of the streets next to the east side of the Forum.

These streets which lie round and east of the Forum suggest a different development. Pompeii may have begun with a little Oscan town planted in what became its south-western corner, near the Water-Gate and the Forum, within the area of Regions II and IV. Here is a little network of streets, about 300 by 400 yds. across (25 acres), which harmonizes ill with the streets in the rest of the town, which lies close to the river-haven on the Sarno, which includes the Forum and Basilica—probably the oldest public sites, though not the oldest surviving structures, in Pompeii—and which is large enough to have formed the greater part or even the whole of a prehistoric city. The earliest building as yet excavated at Pompeii, the Doric Temple, with its precinct now known as the Forum Triangulare, stood on the edge of this area looking out from its high cliff over the plain of the Sarno. Originally this Temple may have stood just within the first town-wall, or perhaps just without it, sheltered by the precipice which it crowns. This area has all the appearance of an 'Altstadt'. No doubt it has been much altered by later changes. In particular, Forum and Basilica have grown far beyond their first proportions, and the buildings which surround them have been added, altered, enlarged out of all resemblance to the original plan. Nevertheless, this theory seems to account better than any other for this curious little corner of streets that are hardly regular even in their relations to one another and are wholly irreconcilable to the rest of the town.

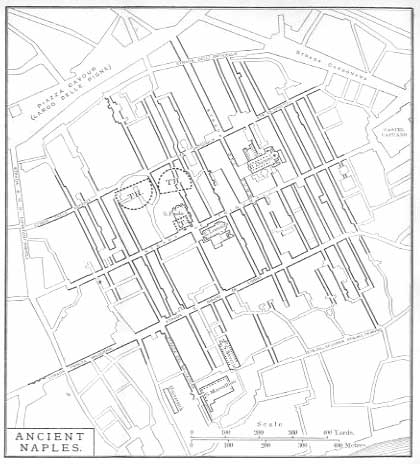

Round this primitive city grew up the greater Pompeii. The growth must have been rather by two or three distinct accretions than a gradual and continuous development. At present we cannot trace these stages. To do that we must wait till the excavations can be carried deeper down, and till the other half of the city has been uncovered, or at least till the lines of its streets and the shapes of its house-blocks have been determined, like those of Priene (p. 42), by special inquiry. All that is as yet certain is that Regions I, III, V, and VI were laid out, and their houses were (in part at least) in existence before—perhaps long before—80 B.C., when the Sullan colony was planted,[49] and we see also that Region VI is planned differently from I and III.